War is peace.

Freedom is slavery.

Ignorance is strength.

Marriage is what Big Brother says it is.

Freedom is slavery.

Ignorance is strength.

Marriage is what Big Brother says it is.

A forum for discussing matters of moment, from a curmudgeonly perspective. (The ideas posted here do not necessarily represent those of any organization with which I am a part). Rude and insulting remarks will not be published, but civil disagreement is welcome.

The Use and Abuse of Humorby A.W. TozerFew things are as useful in the Christian life as a gentle sense of humor and few things are as deadly as a sense of humor out of control.Many lose the race of life through frivolity. Paul is careful to warn us. He says plainly that the Christian’s characteristic mood should not be one of jesting and foolish talking but rather one of thanksgiving (Eph. 5:1-5). It is significant that in this passage the apostle classifies levity along with uncleanness, covetousness and idolatry.

Now obviously an appreciation of the humorous is not an evil in itself. When God made us He included a sense of humor as a built-in feature, and the normal human being will possess this gift in some degree at least. The source of humor is ability to perceive the incongruous. Things out of focus appear funny to us and may stir within us a feeling of amusement that will break into laughter.Dictators and fanatics have no sense of humor. Hitler never knew how funny he looked, nor did Mussolini know how ridiculous he sounded as he solemnly mouthed his bombastic phrases. The religious fanatic will look upon situations so comical as to excite uncontrollable mirth in normal persons and see nothing amusing in them. This blind spot in his make-up prevents him from seeing how badly his own life and beliefs are out of focus. And just so far as he is blind to the incongruous he is abnormal; he is not quite as God meant him to be.Humor is one thing, but frivolity is quite another. Cultivation of a spirit that can take nothing seriously is one of the great curses of society, and within the church it has worked to prevent much spiritual blessing that otherwise would have descended upon us. We have all met those people who will not be serious. They meet everything with a laugh and a funny remark.

This is bad enough in the world, but positively intolerable among Christians.Let us not allow a perverted sense of humor to ruin us. Some things are funny, and we may well laugh sometimes. But sin isn’t funny; death isn’t funny. There is nothing funny about a world tottering upon the brink of destruction; nothing funny about war and the sight of boys dying in blood upon the field of battle; nothing funny about the millions who perish each year without ever having heard the gospel of love.It is time that we draw a line between the false and the true, between the things that are incidental and the things that are vital. Lots of things we can afford to let pass with a smile. But when humor takes religion as the object of its fun it is no longer natural—it is sinful and should be denounced for what it is and avoided by everyone who desires to walk with God.Innumerable lectures have been delivered, songs sung and books written exhorting us to meet life with a grin and to laugh so the world can laugh with us; but let us remember that however jolly we Christians may become, the devil is not fooling. He is cold-faced and serious, and we shall find at last that he was playing for keeps. If we who claim to be followers of the Lamb will not take things seriously, Satan will, and he is wise enough to use our levity to destroy us.I am not arguing for unnatural solemnity; I see no value in gloom and no harm in a good laugh. My plea is for a great seriousness which will put us in mood with the Son of Man and with the prophets and apostles of the Scriptures. The joy of the Lord can become the music of our hearts and the cheerfulness of the Holy Spirit will tune the harps within us. Then we may attain that moral happiness which is one of the marks of true spirituality, and also escape the evil effects of unseemly humor.

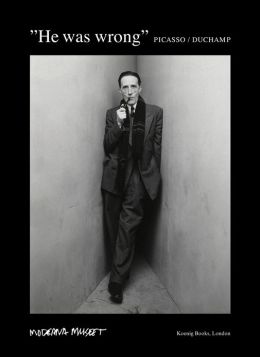

This and another recent book have made much of the rivalry and antipathy between Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Marcel Duchamp, (1887-1968), two of the most influential, iconoclastic, and controversial artists of the twentieth century, although Picasso was immeasurably more popular and wealthy. (See also Larry Witham, Picasso and the Chess Player: Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, and the Battle for the Soul of Modern Art [2013].) Picasso and Duchamp did not like each other; neither did they share a philosophy of art (if Picasso even had one). Hence, when Picasso heard that Duchamp had died, he promptly and laconically said, “He was wrong.” Had Duchamp outlived Picasso, the epithet (or something like it) probably would have been repeated. There was no meeting of minds (or paints or sculptures) to be found here between the Spaniard (who settled in France) and the Frenchman (who settled in America). This volume was published on the basis of an exhibit at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden (as are many art books).

This and another recent book have made much of the rivalry and antipathy between Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Marcel Duchamp, (1887-1968), two of the most influential, iconoclastic, and controversial artists of the twentieth century, although Picasso was immeasurably more popular and wealthy. (See also Larry Witham, Picasso and the Chess Player: Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, and the Battle for the Soul of Modern Art [2013].) Picasso and Duchamp did not like each other; neither did they share a philosophy of art (if Picasso even had one). Hence, when Picasso heard that Duchamp had died, he promptly and laconically said, “He was wrong.” Had Duchamp outlived Picasso, the epithet (or something like it) probably would have been repeated. There was no meeting of minds (or paints or sculptures) to be found here between the Spaniard (who settled in France) and the Frenchman (who settled in America). This volume was published on the basis of an exhibit at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Sweden (as are many art books).